Edgewater Stonemasons President Craig Beattie recently began writing a series of articles for the Frontenac Heritage Foundation’s periodical entitled “From the Banker”. The following is the first in a two part series on stone bonding of the Kingston area:

From the Banker

The term ʻbankerʼ refers to a bench or table traditionally used by stonemasons for cutting stone; the purpose of this and future articles is to share the lessons that I have learned working as a stonemason on conservation projects across Canada. It is my hope to give interested parties greater insight into the noticeable and not so noticeable qualities of the brick and stone masonry that defines Kingstonʼs built heritage, and to promote the best practices for conserving this irreplaceable resource.

To readers of this publication, stone ʻbondingʼ may or may not be a familiar concept. It is a term that is used quite simply, to describe the arrangement of stone within a wall. It can tell us interesting things about the structural qualities of our historic buildings, and it goes to the heart of their visual appearance. Bonding is comprised of two separate but overlapping categories: face bonding, which is concerned with the visible arrangement or pattern of stone in a wall for aesthetic purposes, and bed (or structural) bonding, which is the strategic placement of large stones throughout a wall to increase its structural integrity. In this, the first of a two part series, we will examine how the appearance of a stone building is shaped by its face bonding, and look at some of the more prevalent styles in the Kingston region.

A physical characteristic of a masonry wall that helps to define its appearance, face bonding tells us much about the time period and the people involved in its construction. The variety of patterns are often synonymous with different architectural styles, and are a tool at the architectʼs disposal for conveying messages about the buildingʼs intended purpose. Historically, it also had much to do with practical considerations in terms of the sort of stone available, and the ownerʼs budget. In cases where it was left up to the builders to decide, their regional backgrounds whether English, Scottish or Irish would often times inform the decision. Although varying greatly in their overall appearance, there is one common element among all well-executed bonding styles, and that is the control of vertical joints within a wall to create stability. It was long ago determined that long vertical stretches between stones (stack joints) created a weak point in any wall, and that this could be avoided by overlapping the stones to tie each one into the next.

The following list of bonding styles is by no means exhaustive, but is intended to showcase some of the more prevalent styles in the Kingston area.

Random Rubble: This is a bond that is often referred to as the most beautiful style, as it makes use of a complete assortment of stone shapes and sizes. It can be seen all over Kingston, and exposed interior limestone walls are almost exclusively random rubble. A mason building in this style would essentially place stones in the wall as they come to hand, creating a random look that highlights the natural elements of the material. Donʼt let the name fool you though; although the appearance may be random, the style still conforms to the basic rules of stonework. Vertical joints are interrupted as often as possible, stones are placed with their greatest depth into the wall, and sedimentary stones are laid along their natural bedding plane. The modern appreciation for random rubble

represents a cultural shift, and would likely have been amusing to early masons; it was the most economical style since it utilized whatever material was available and required the least amount of labour and skill on the masonʼs part. At a time when mass production of material was in its early stages, there was a high value on creating uniformity, which required time and money, and was a reflection on the masonʼs mastery over the material. Today, we view the irregularity of stone as an admirable quality, while producers of manufactured stone spend fortunes (and fail) trying to replicate the unique natural qualities of the material.

Coursed Rubble: Seen in many of this areaʼs Ontario Cottages, coursed rubble refers to a continuous run of stone at the same height across the length of a wall. This creates a ʻcourseʼ of stone with a full uninterrupted horizontal joint, and each vertical joint in the stonework is broken by adjacent stones on the next course. This style would require that builders sort through their supply and use only stone that met the height requirements, which in this area was often 5-6”, commonly available in local quarries. Although the weathered grey patina of our heritage limestone buildings does not display any obvious tool marks, much of the coursed rubble in this region was originally finished with a ʻpunched faceʼ which refers to a technique of flattening a stone using a ʻpunchʼ, a long pointed masonʼs chisel. Many Ontario Cottages feature a coursed rubble bond at the front of the building, and random rubble stonework along the sides and back. This reflects the added importance placed on the front entrance of the house, the most visible section to visitors or passers-by.

Snecked Rubble: Seen in many of this areaʼs formal buildings such as churches and estates, this is a high-skill form of stonework that requires a significant amount of labour. The principle tenet of this style is that small stones called snecks are used to separate stones of different heights. Snecks are used in conjunction with levellers (the majority of the face stone) and jumpers, which are large squared stones placed in a balanced manner throughout the wall. The overall effect is visually pleasing, and creates probably the most structurally sound bond because of the way horizontal and vertical joints are broken. It is also referred to as Scotch-bond, and can be found all over Scotland; it has been suggested that this styleʼs origins may be traced to the defensive fortifications there, where builders were looking for innovative ways to resist the English and their effectiveness at dismantling castle walls. Unfortunately it is one of the most misused styles, as many of its rules and intricacies are not widely known by todayʼs masons. Snecked rubble can range in appearance from highly ordered to rustic depending on the type of stone used.

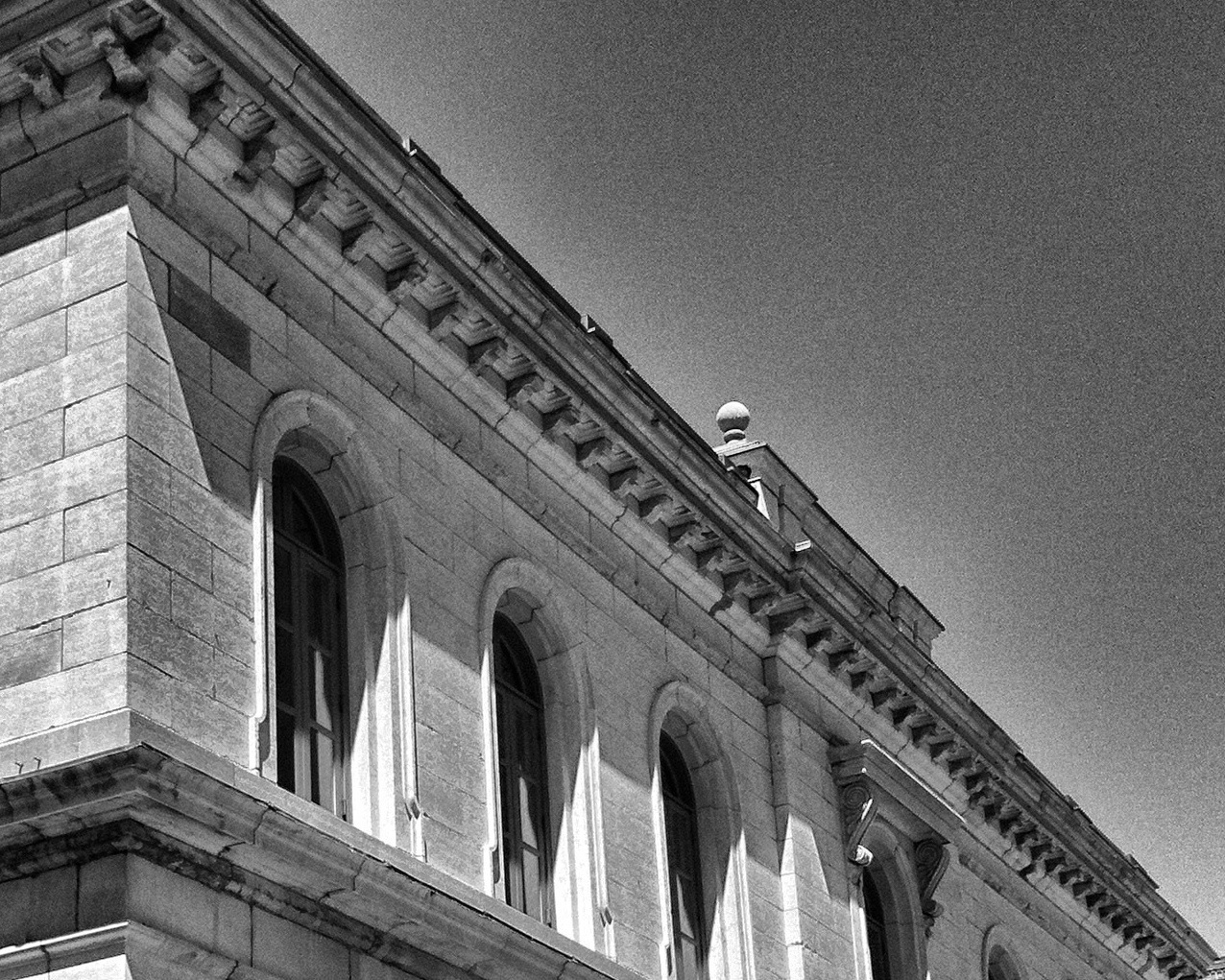

Ashlar: This style of work is known for its clean lines, and highly structured order. Each stone is finished to a very narrow set of tolerances, with an emphasis on squareness and uniform surfaces. The stone can be finished smooth or with decorative finish, and is typically arranged in a coursed pattern. It is the most labour-intensive bond as well as the most homogenous, and would have required a strong skill set to transform the natural blocks of stone into a finished product.

Next time…

The lasting durability of our built heritage can be attributed to three interconnected qualities: Design, workmanship and materials. Structural bonding is a hidden aspect of a solid stone wall that encompasses all three, and is essential to itʼs longevity. In part two of our series on bonding, we will examine the anatomy of such a wall, and identify the key places that stone is used to maximize structural integrity.

Founded in 1972, the Frontenac Heritage Foundation (FHF) is a non-profit organization created to promote the preservation of buildings that contribute to the heritage of Kingston, Ontario, the County of Frontenac and the Islands, and Loyalist Township. For more information visit: www.heritagekingston.com